Nation State

by Hannah Kaercher

The idea for this keyword first came to me in the first few days of the Trump Administration. I saw the headlines talking about the potential for mass deportations around the country, and this gave me pause. Then, I saw how Trump framed some of his logic within the context of the Alien Enemies Act of 1798. [1] This act gives the president authority to deport any people that are deemed to be enemies of the country, an act that, according to NPR, has both "gotten relatively little attention, let alone use, in the more than 200 years it's been on the books," and has only been invoked during wartime. This made me wonder, how can a nation whose existence is based solely on the dispossession of Indigenous land define who is legal and who is an "Alien?" What gives the United States the right to claim, and eject people, from stolen land? How can a nation-state claim to have enemies when its whole existence is facilitated through its actions as an aggressor towards Indigenous communities.

My original idea was to think about how the definition of the nation-state itself tends to be unfounded. The nation-state itself is a Western concept that is used to make claims to legitimacy. However, my work with this topic has expanded the viewpoint of the piece itself. I am instead using the idea of the nation-state to understand how the term influences geography and sense of place, especially in education. I also wanted to use this as an opportunity to confront the problematic aspects of my own education, specifically how I understood my environment growing up. Given my own identity, I cannot, nor would I want to, speak to the experiences of Indigenous people in what we know to be the United States. I can only confront my own privileges and experiences in the hopes of furthering dialogue on this subject.

It is important to begin with how the nation-state is defined. Although the term itself is used very broadly and frequently, it is one that is difficult to fully understand the meaning of. People often use the terms state, nation, and nation-state interchangeably when referring to the United States. "State, Nation and Nation-State: Clarifying Misused Terminology," attempts to make sense of each term's individual meanings. States are defined to be "tied to territory," with a "sovereign or state as absolute authority over territory."[2] Nations are a "group of people who see themselves as a cohesive and coherent unit based on shared cultural or historical criteria."[3] The definition of nation-state is a combination of the previous ideas. Here, the nation state is described as " a homogenous nation governed by its own sovereign state—where each state contains one nation." [4] The three different terms are linked through the idea of territory and identity, presenting the idea of borders and homogeneity as a requirement to fit these definitions. Existence as a nation-state is linked to control over a territory, its people, and ideas. The nation-state itself can only exist through a means of conquest and occupation. Defining the nation-state through its inherent need to conquer the geographic landscape will help frame how the nation-state influences the understanding of geography and sense of place for many residents of what we now know as the United States.

Colonial narratives that impact geography and sense of place can be observed in any town in the United States. For the purposes of this keyword piece, I will be using my hometown of Fayetteville, NY. Fayetteville is located in Onondaga County, the ancestral homeland of the Haudenosaunee people. During my upbringing, the Haudenosaunee were just an afterthought in favor of the colonial history of New York. We learned about the Haudenosaunee in fourth grade, speaking about their democracy, the "three sisters" of corn, beans, and squash, and how they played lacrosse. This largely surface-level content portrayed the Haudenosaunee as merely a footnote, an almost obligatory reference to the people that came before the colonists. As fourth graders, we never really processed how our geographic history was problematic. We went on with our days, even participating in a final project in this "unit," where many students dressed as Indigenous people to "celebrate" Haudenosaunee culture. In the first 13 years of my schooling, this unit was the only time we spent speaking about the Haudenosaunee.

Understanding the broader colonial legacy of Fayetteville, NY can be done through a drive down Sweet Road. This is the location of the YMCA "Camp Evergreen," a place where many of the village's kids go in the summers. However, this camp went by a very different name from its founding in 1933 up until 2021. The camp was formerly "Camp Iroquois," utilizing a derogatory name for the Haudenosaunee people. Most children in elementary school, myself included, thought nothing of this name's connotations. To many kids, this was just a fun place they went in the summer. The 2021 announcement on the name change refers to it as a "Long-Overdue Change for [the] Camp."[5] The YMCA describes its motivation behind the choice as the desire to "remedy the error of [its] past,"[6] framing the decision as one that will forever rewrite the colonial history that has pervaded both the camp and its surrounding area. This attempt to erase rather than confront the past is indicative of the lack of understanding about how deeply colonialism impacts geography and sense of place. Fayetteville's very geographic existence is a direct result of the dispossession of Haudenosaunee land, yet this camp utilized a derogatory name, misappropriating Indigenous culture for almost a century. Can geography be fully understood without recognizing the colonial legacy of the nation state?

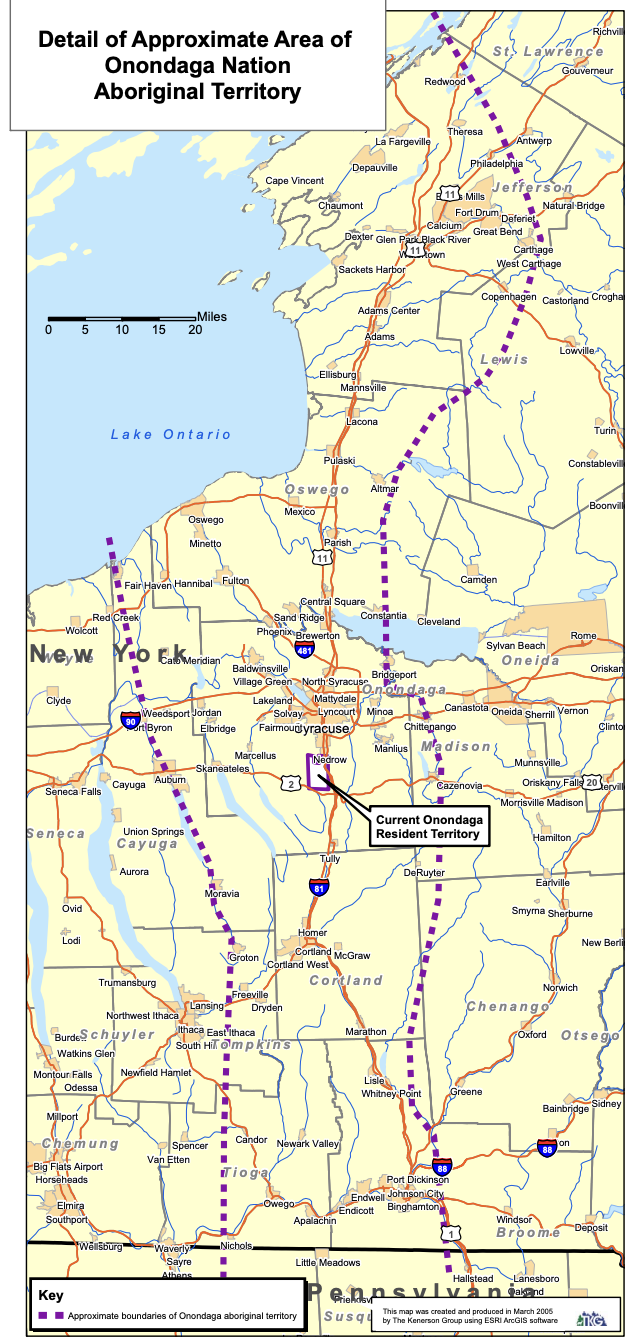

Figure 1[7]

The drastic effects of colonial occupation in Onondaga County can be seen by comparing the large area of the Onondaga Nation's aboriginal territory to its small current boundaries. Today, the area depicted is known as part of New York, with the existence of the Onondaga Nation often being relegated to an afterthought. It's almost never recognized how what we know to be Onondaga County only exists due to the dispossession of Indigenous land. This provides a lens through which to view just how strongly the nation-state alters how geography is remembered and understood. The land is merely reduced to be the "property" of New York, and the larger United States. The Onondaga Nation tried to fight back against the reduction of the territory to New York property through the Land Rights Action in 2005. This map was created for this petition, which argued that New York violated federal law when it took Onondaga land. [8] The eventual ruling of the case in favor of New York is telling of just how deeply entrenched the commodification of land is in Western understandings of geography and sense of place. Western law continues to uphold these colonialist understandings of territory.

Figure 2 [9]

The issue of the commodification of land is one that exists throughout the United States. The expansion of the United States is presented as the transactions between nation-states, further cementing the idea of claim in the understanding of geography.[10] The purpose of this map is educational, and it is meant for school-age children to help them learn about U.S. geography. This map could be encountered by any student of U.S. history class across various parts of their schooling. Students are actively being taught the logics of colonialism and the nation-state using maps that give no recognition to the existence of Indigenous communities. For example, the map presents the "Louisiana Purchase" as a result of the U.S. "buying" the land from France, reducing the land to a commodity that can be bought and sold. This purchase triggered a large-scale expulsion of many Indigenous people, yet this is omitted in favor of demonstrating how the land was bought from France. This shows how the logic of the nation-state presents U.S. geography as important only through how it could be ceded, conquered, and owned.

Figure 3[11]

This expansionist perspective in regard to geography is presented the clearest through the lens of "Manifest Destiny," the logic that the United States used in its attempts to justify its expansion in the early 19th century. Manifest Destiny implied that the United States had been preordained, likely by God, to expand its borders and influence. An image often synonymous with Manifest Destiny is "American Progress," which depicts the westward movement of the American people in the 19th century.[12] The term "progress" implies moving forward, an America that is not only growing in size, but opportunity. However, this "progress" is contingent on the dispossession of Indigenous land. Dispossession is alluded to through the inclusion of a group of Indigenous people being forced out of their homes in the background. "Progress" takes on the new meaning of conquering the landscape for the nation-state, often with no regard for the people who already inhabit the land. The Indigenous people in the painting are relatively small in comparison to Columbia and the larger landscape, presenting them as an afterthought in the larger narrative of expansion. They are a footnote, only another group to be conquered and sent away in favor of "American Progress."

In spite of the nation-state's attempts to claim territorial legitimacy, the ideas and work of Indigenous people deconstruct the narrative that links geography to territorial claim. In "Land as Life: Unsettling the Logics of Containment," Mishauna Goeman describes the reduction of land to property as the "[logic] of containment." Containment facilitates the loss of rights and sovereignty using the laws and ideology of the nation-state. In contrast to containment logics, Goeman explains, Indigenous methods "[think] through land as a meaning-making process rather than a claimed object."[13] Goeman's reframing of land as a meaning-making process presents a new way to view its purpose. Through this lens, land becomes important through its ability to shape culture and facilitate sovereignty. Land is a place for meeting, exchange, and working together rather than a possession. In Indigenous Studies, Goeman explains, "[land] is a resistance to the conception of fixed space."[14]This rejection of fixed space transcends the territorial and legal claims that the nation-state uses to define its borders. If land is to reject fixed space, the idea of borders is antithetical to both its meaning and purpose. The Indigenous redefinition of land's meaning beyond the idea of territorial claims allows for the deconstruction of the "containment narrative" that the idea of the nation state often presents.[15]

The Inupiat People in Alaska are just one of the many Indigenous communities that are deconstructing the territorial logics of the nation state. In "Inupiat Naming and Community History: The Tapqaq and Saniniq Coasts near Shishmaref, Alaska," Susan Fair identifies how in spite of significant dispossession, "the loss of land, or even of ancestral home, is not poignant [to the Inupiat people]," since "what matters are the kinship ties of the people with each other and the names, memories, and histories that remain." [16] Here, land is shown to be a place of meaning making, important through the histories, memories, and relationships that were created. The land facilitated connections between people that will always remain. This presents the idea of land "loss" as a Western construct, only "poignant" through the lens of containment logics and territorial claim. The removal of claim entirely from the importance of land, presents a narrative largely contrary to this Western logic.

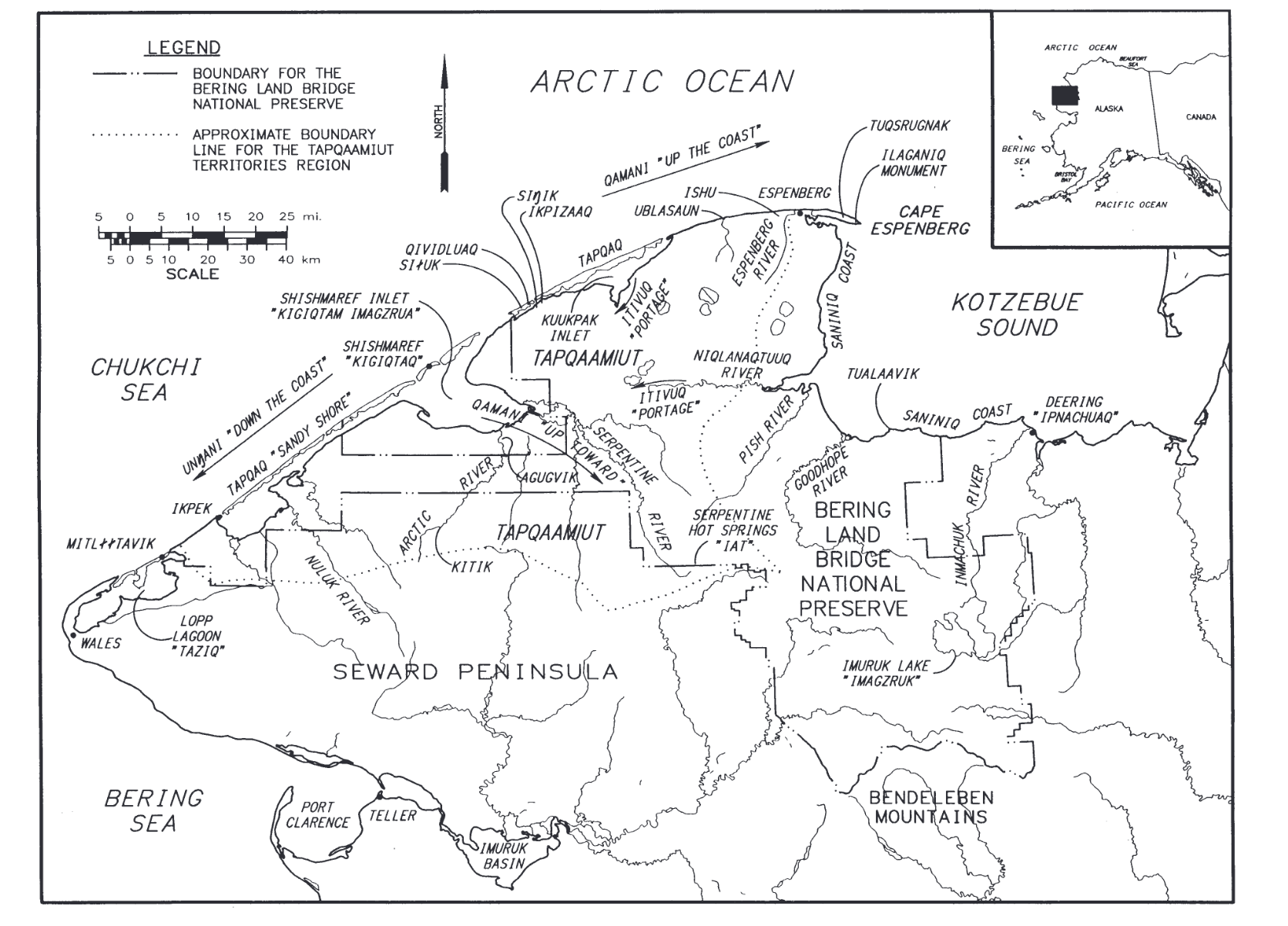

Figure 4

The idea of land's importance through shared histories is reflected through the Inupiat place-naming shown by the map.[17] Place-names reflect how land is understood as texts. Fair identifies three of these categories as family texts, creation texts, and memory names.[18] Each of these categories demonstrates the meaning of land as one indicative of relationships and histories, not ownership. "Family texts" are representative of land that "[defines] this family as shaped by that place." [19] The place is important not because it was inhabited by certain families, rather their identities were formed by connection to the land. "Creation texts" designate land to be instrumental in "[bolstering] national identity." [20] These names are indicators of how Inupiat people came to be, combining both myth and legend to establish a sense of place. The final category for naming, memory names, is often used to represent places that are no longer there, but the"tales associated with them [are] sometimes substitute for the place itself." [21] The land itself doesn't need to be inhabited or claimed to be important, its significance is preserved through storytelling and relationship building. These names reclaim the idea that land is only significant through its role as property of the nation state and its peoples. Land matters not because of claim, but because of the connections and heritages that were fostered there.

It is often the easiest to get overwhelmed by the information around us. The actions of conquest and expulsion utilized by the Trump Administration are terrifying actualizations of the nation-state's power over the land. However, it is important to see how these logics are constantly being challenged and unsettled. The land itself is not important within the context of the United States, it has meaning through its connection to family, history, and memory. The work of Indigenous scholars is integral to fostering resistance against policies that have sought to destroy the purpose of the land. Although there is still much work to be done in recognizing the effect of the nation-state on geographic understanding, furthering dialogue on this topic has never been more important.

Footnotes

[1] Treisman, Rachel. "Trump is Promising deportation under the Alien Enemies Act of 1798. What is it?" NPR. 19 October, 2024. https://www.npr.org/2024/10/19/nx-s1-5156027/alien-enemies-act-1798-trump-immigration

[2] "State, Nation and Nation-State: Clarifying Misused Terminology." Penn State College of Earth and Mineral Sciences, accessed 7 February 2025. https://www.e-education.psu.edu/geog128/node/534

[3] ibid

[4] ibid

[5] YMCA of Central New York. 2021. "A Long Overdue Change for our Camp." https://www.ymcacny.org/blog/long-overdue-change-our-camp

[6] ibid

[7] Onondaga Nation. "Maps of the Onondaga's Land Rights Lawsuit" Accessed 7 February 2025 https://www.onondaganation.org/land-rights/maps/

[8] Onondaga Nation. "Maps of the Onondaga's Land Rights Lawsuit" Accessed 7 February 2025 https://www.onondaganation.org/land-rights/maps/

[9] Crofutt, George A. American Progress. , ca. 1873. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/97507547/.

[10] ibid

[11] ibid

[12] ibid

[13] Goeman, Mishuana. “Land as Life: Unsettling the Logics of Containment.” In Native Studies Keywords, edited by STEPHANIE NOHELANI TEVES, ANDREA SMITH, and MICHELLE H. RAHEJA, 71–89. University of Arizona Press, 2015. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt183gxzb.73

[14] ibid, 74

[15] ibid

[16] Fair, S. W. 1997. “Inupiat Naming and Community History: The Tapqaq and Saniniq Coasts near Shishmaref, Alaska.” Professional Geographers 49(4): 466–80.

[17] ibid

[18] ibid

[19] ibid

[20] ibid

[21] ibid