Orang Laut

by Kate Yeo

“In the last days of the settlement on Sakeng, when the entire community was being relocated, there was a palpable mood of grief and loss. The once house-proud villagers reluctantly left the houses they had built for themselves to go to wreck and ruin ... They sold their boats, thereby giving up their means of transport on the sea. Their relocation from Sakeng to Singapore was not just a move from a small island to a bigger island. More fundamentally, it ended an indigenous way of life oriented towards the sea that had existed since long before the British colonisation of Singapore.”[1]

—

Singapore’s Semakau Landfill is often described as an engineering marvel.

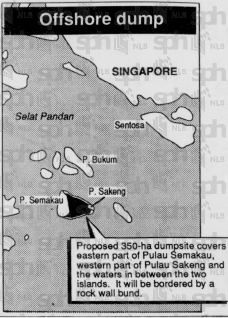

Located a 45-minute boat ride away from mainland Singapore, it is the world’s first offshore landfill, constructed in 1995 by merging two islands: Pulau Semakau and Pulau Sakeng. (Pulau means “island” in Malay.) Today, Semakau co-functions as a storage site for Singapore’s incinerated waste, a habitat for native biodiversity, and a recreational destination. “Visitors to the island … might expect foul odours and swarms of flies,” described one journalist, “but instead they are greeted with stunning views of blue waters, lush greenery and wildlife.”[2]

Image 1: A map of Pulau Semakau and Pulau Sakeng in relation to mainland Singapore, 1989.[3]

As someone born into 21st-century, metropolitan Singapore, I was only ever taught of Semakau as a distant dumping ground. Digging into Singapore’s archives, however, I learned that Pulau Semakau had once been earmarked for the development of a petrochemical complex. Although this project never materialized, a parliamentary document from 1975 indicates government approval for the complex,[4] marking the moment Pulau Semakau became a site of capital expansion. The transcript shows a minister describing the island as a “swamp, foreshore and seabed”—reminiscent of the “empty land” myth long wielded by colonizers to justify land dispossession. But the minister omitted a crucial fact: Pulau Semakau was home to the Orang Laut.

Who are the Orang Laut?

The Orang Laut, or “People of the Sea,” are the original inhabitants of Singapore. A nomadic maritime people, they have traversed the waters of Southeast Asia for centuries and are scattered across the region today. Singapore’s Orang Laut tribes include the Orang Selat, Orang Kallang, and Orang Seletar. While each community has distinct cultural practices, they share an instinctual orientation towards the water. Traditionally, Orang Laut spent most of their lives at sea, fishing in waterways and foraging in mangroves.[5]

Image 2: Singapore’s Orang Seletar in the 1950s. Image by Dr Ivan Polunin, via BiblioAsia.[6]

The Orang Laut’s ties to the seascape were documented as early as the 15th century. Ming dynasty records describe the Orang Laut guiding Chinese ships through the dangerous waters around Southeast Asia.[7] They were “skilled navigators and fierce fighters,” deftly moving through the Straits of Malacca and allying with Malay rulers to defend entrepôts from attacks by neighboring rivals.[8] The Orang Laut also supplied valuable sea products, such as tortoiseshells and pearls, for trade.[9]

However, power struggles among Malay sultanates throughout the 17th and early 18th centuries led to the fragmentation of Orang Laut communities. From the late 1780s, the arrival of the British in Southeast Asia, with their new steamships and navigational charts, further eroded the Orang Laut’s role as indispensable navigators.[10] By this time, Orang Laut communities had dispersed across southern Peninsular Malaysia, Indonesia’s Riau Islands, and what Singapore now calls the Southern Islands.

Image 3: Map of Singapore’s Southern Islands, undated.[11]

Details on life was on the Southern Islands are scant, albeit kept alive through anthropological fieldwork conducted in the 1980s, news archives, and personal anecdotes shared by Orang Laut descendants. I learned that residents enjoyed fresh seafood, built their own boats, and cultivated coconut. Their houses were built on stilts, half over the sea and half on land, rooting them, quite literally, to the water.[12] Rohani Rani, a third-generation Orang Laut who grew up on Pulau Semakau, says that their way of life was “full of happiness. … Even though it was tough, we were happy.”[13] Rohani describes Semakau as full of kampung (village) spirit—a term harkening back to Singapore’s early post-independence years, before high-rise apartments supplanted villages, and when kinship and community thrived. The kampung spirit has often felt like an abstract notion—a thing of the past—to me, but for Rohani, it encapsulates Pulau Semakau’s former vibrant communal culture. For instance, during Hari Raya, a festival celebrated by Muslims worldwide at the end of their month of fasting, residents would make traditional Malay desserts together.[14] Similarly, a 1981 news article on Pulau Sakeng describes how on special occasions like weddings or a birth in the family, everyone on the Island would be invited.[15] The sense of camaraderie extended across the waters: residents of the Southern Islands gathered annually for a friendly sports competition known as the “Pesta-5” (Pesta: “Carnival”), which included tug-of-war, swimming, and sampan (small boat) races.[16]

Image 4: I intentionally blurred this image to avoid copyright implications. As certain local news archives cannot be accessed remotely, photos of this article from 1981 were taken on a library monitor in Singapore and sent to me. The image shows several boys jumping off a jetty in Pulau Sakeng. The full caption reads: “Fun and frolic … After school, the village boys love to dive off the jetty. But beware of the ikan lepu or stone fishes. They lie motionless on the reef-bed and give a painful sting to the unwary.” Image by David Tan, via New Nation.[17]

Unpacking State Narratives on the Orang Laut

Despite the Orang Laut’s deep roots in Singapore, I was unaware of their existence until 2020, when I came across a social media post by an Indigenous advocacy group.

The standard “Singapore Story,” disseminated for decades through schools and ministerial speeches, goes something like this. In 1819, British official Stamford Raffles set foot in the sleepy fishing village of Singapore. Under his leadership, the island grew into a “thriving settlement.”[18] Following the second world war, in 1963, Singapore joined neighboring territories to form the state of Malaysia, bringing an end to 144 years of British colonial rule. However, racial and political divides culminating in violent riots ended the short-lived merger, thrusting Singapore into independence in 1965. Nearly 70% of the population lived in slums,[19] the country had no natural resources, and, according to then-Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew, was surrounded by “hostile” Malay-majority states.[20] Singapore must fight for its survival, Lee’s government continuously emphasized. By the 1990s, however, Singapore’s GDP per capita had increased nearly 50-fold.[21] This growth was driven in large part by foreign investment—including through the country’s new role as a global petrochemicals hub. Innovative projects like the Semakau Landfill further cemented Singapore’s status as a “modern” city.

As other scholars have pointed out, the 1819 colonial start date in this historiography “intentionally [de-emphasizes]” Singapore’s historical roots in the Malay world.[22] Michael Barr argues that because Singapore’s establishment as an independent state was rooted in tensions between the dominant Chinese population and Malay minority, the state sought to delegitimize Malay claims as owners on the island, therefore deliberately “[expunging] its pre-colonial history from public consciousness.”[23] Consequently, Singapore accords no recognition to the Orang Laut for their generations of living and trading in the region, instead celebrating colonial figures like Raffles. Today, an eight-foot-tall statue stands on Raffles’s supposed landing site along the Singapore River—and in 2024, as colonial statues around the globe were coming down, yet another public statue of Raffles was erected in Singapore.[24]

The second implication of the state’s historical script is that it rationalizes mass dispossession on Singapore’s offshore islands. Post-independence, the government’s narratives of scarcity and survival took hold in the national psyche, legitimizing the Orang Laut’s forcible displacement to make way for new manufacturing hubs in the name of “growth.” In 1977, Pulau Semakau’s 600 islanders were resettled to public flats on the mainland; in 1993, Pulau Sakeng—by then, Singapore’s last indigenous settlement—was vacated to make way for the construction of Semakau Landfill.

In fact, this pattern of forced resettlement predated independence. When the British arrived in Singapore in the 19th century, they had forced the Orang Gelam, an Orang Laut tribe, to relocate further inland, away from their original settlements at the mouth of the Singapore River.[25] Singapore’s history demonstrates how colonization takes place on multiple timelines and scales, and by multiple perpetrators; independence led not to a process of decolonization, but instead further marginalized the Orang Laut. Consequently, we must question: independence for whom?

For the Orang Laut, moving to mainland Singapore truncated their ties to the sea, and by extension, an integral part of their identity. News archives from 1993 note how older residents on Pulau Sakeng were “most reluctant to leave a lifestyle that they, their fathers and forefathers have known all their lives.”[26] One interviewee explained: “Here there’s fresh air and company. In a [public] flat, we can only move down the flat and up again.” In a 2020 interview, Rohani Rani, who moved from Pulau Semakau in 1977, described the challenges of assimilating into city life: “We didn’t understand anything. Seeing cars on the roads were something we’d never seen before. We didn’t know how to navigate our way through the city.”[27] Forced assimilation has been well-established in Native studies as a form of structural violence,[28] as the process systematically strips Indigenous peoples of their traditions and forces them to adopt settler norms, thereby disrupting the reproduction of cultural knowledge across generations. But it is further important to consider here the individual, embodied experience of colonial violence. For the Orang Laut, state power was enacted on the bodily level in denying them the right to breathe the island air they were used to, and in the chronic stress of living in a state of enforced placelessness.

Importantly, the 1993 news article highlights a generational divide, with younger residents on Sakeng ostensibly adopting a more “pragmatic” view of resettlement. For instance, then 32-year-old Rashidah Ahmad, who worked as a factory operator on the mainland, said, “At least I can make sure my small sons get good schooling. You can’t afford to remain uneducated now.” One could argue that with Singapore’s “modernization” process, changing perceptions of a “good life” trickled down to younger members of the Orang Laut community—from this perspective, the Orang Laut were choosing to leave their culture behind. However, individual choices to relocate must be situated in the context of new urban pressures, particularly the rising cost of living and a state-driven “productivity campaign.” Following independence, the Singapore government had placed increasing emphasis on labor-driven economic activities and workforce efficiency, establishing a National Productivity Board to “instill a culture of productivity” and even disseminating key chains and car decals with the slogan “Productivity Is Our Business.”[29] As value in Singapore came to be defined by people’s contributions to the economy, it is no wonder that certain organizations of social life—such as wage labor and formal schooling—became naturalized, while the Indigenous way of life on the sea was stigmatized. This privileging of certain modes of existence over others is far from just a side effect of “development”; it is, in fact, central to the status quo, and lies at the core of the global colonial project, as reflected in the ugly legacies of American Indian residential schools, Australia’s Stolen Generations,[30] and in Palestine today.[31]

Singapore’s leaders were not blind to the social implications of resettlement. In 1993, as Pulau Sakeng was being slated for landfill development, a Nominated Member of Parliament raised the question of cultural preservation. I include an excerpt of that exchange here:[32]

Dr Kanwaljit Soin (Nominated Member): Sir, is the Minister aware that Pulau Sakeng is the last Malay kampong [village] and is a very valuable part of our cultural heritage and that an economic value cannot be put on an inadvertent destruction of our cultural heritage?

Mr Abdullah Tarmugi (Minister of State for the Environment): The Ministry is aware of this fact. But … if Pulau Sakeng were to be excluded … we would need to spend altogether an additional sum of $130 million over and above the $1 billion that we are going to spend to build this landfill site.

This debate further underscores how Singapore’s Orang Laut were not simply forgotten, but erased.[33] Erasure was a calculated decision, underpinned by the state’s capitalist impulse which saw “land” solely as an asset, rather than a place of communal ties and resilience. Dispossession was, in other words, built into the fabric of capitalist urbanization. In this economic order, Indigenous lives were deemed marginal to the Singapore Story. It would be another 30 years before the Orang Laut were referenced in Parliament again.

What does Orang Laut resilience and resistance look like?

In 2023, Member of Parliament Nadia Samdin explicitly recognized Singapore’s Southern Islands as once “part of the lively settlements of Orang Laut,” and called for sensitivity to the cultural significance of these spaces in light of new development plans.[34] This milestone—the first time that “Orang Laut” was ever uttered in Singapore’s Parliament—came amidst a groundswell of Indigenous-led activism which took off during the pandemic, and continues to gain momentum.

Crucially, the revitalization of Orang Laut culture in Singapore is taking place in spite of, rather than because of, the state. In 2021, Firdaus Sani, a fourth-generation Orang Laut whose family is from Pulau Semakau, founded Orang Laut SG—a home-based food delivery business showcasing Indigenous cuisine, which has since expanded into an advocacy platform centering his community’s stories and culture.[35] Firdaus’s initiative has gained considerable attention in Singapore’s mainstream media, from printed interviews to mini documentaries, calling into question Singapore’s sanitized national narratives.

Calls to protect Orang Laut heritage are not new to Singapore. My archival research uncovered how in the last years of Pulau Sakeng, Singaporeans wrote to local newspaper forums to argue against the island’s development. “Would it not be possible to … promote [Pulau Sakeng] as a living example of our Malay heritage instead of destroying it?” questioned one writer in 1986.[36] “Pulau Sakeng is too valuable a cultural asset to be sacrificed for the landfill scheme. Its value is immense but cannot be quantified,” wrote architectural professor Edmund Waller in 1993.[37]

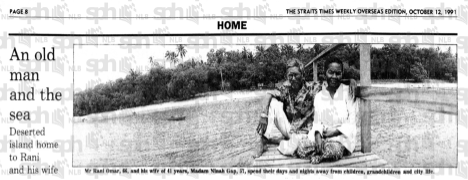

Further, in a most powerful act of resistance, one Orang Laut islander chose to return to Semakau shortly after his forcible resettlement. In 1977, two weeks after moving into a flat on mainland Singapore, Rani Omar returned to Pulau Semakau—his birthplace and home. “This island gives me freedom and I feel so much more healthy,” he later explained in a news interview.[38] For decades, Rani lived alone on the deserted island, spending his days fishing, swimming, and cooking simple meals on a kerosene stove. His wife Ninah joined him twelve years later, once their children could care for themselves on the mainland.

Image 5: Screenshot of an article about Rani Omar living on Pulau Semakau.[39]

I cannot pretend to know Rani’s thought process then—but if I were to hazard a guess, I imagine in his mind, he was simply returning home. Yet, as a young Singaporean looking back today, and having grown up in a culture of heavy repression and self-censorship, I am filled with immense gratitude and admiration for Rani’s act of defiance. In choosing to ignore the government’s resettlement order, he was subverting the state’s disproportionate power and reclaiming his own agency. It is not so much the fact that he returned that stands out to me, but rather that he carved out a choice to return. His decision also articulated what government leaders had failed to understand: that the Orang Laut had a deep bond with land and water that could not be nurtured in the city. I later found out through reading an online interview that Rani Omar is Firdaus Sani’s grandfather.[40] Resistance runs in their blood!

What does it mean to be Orang Laut in Singapore today? I posit that it means carrying on Rani’s legacy of fighting back and asserting their existence. Today, Firdaus’s family continues to fish and forage—such as for mussels and gong gong (sea snails)—in Singapore’s coastal waters.[41] Their cuisine is still based on the vegetables and seafood that could once be collected from Semakau. In a society reliant on air-conditioned grocery stores, these practices sustain Orang Laut epistemologies and ways of relating to the water. More broadly, through media features such as mini documentaries, the Orang Laut ensure that their community’s cultural practices are captured in Singapore’s historical record. Such stories serve as a powerful humanizer: they disrupt the notion that Singapore was terra nullius, or that Indigenous people are “extinct” or “backward.” For example, as one interviewer pointed out, foraging is a particular skill that can only be learned over time with an intimate understanding of the natural world.[42] It is far from primitive. Orang Laut SG is therefore both about a retelling of history from the bottom-up, and the shaping of history as it is being written in real-time.

Image 6: Screenshot of a video showcasing the Orang Laut’s foraging practices. Here, Firdaus’s mother Nooraini is looking for shellfish.[43]

Admittedly, however, ongoing advocacy efforts have not yet translated to the material return of the Orang Laut land and water. Tuck and Yang famously declared that decolonization is not a metaphor;[44] yet, no group in Singapore—at least, to my knowledge—is explicitly calling for a return of the Southern Islands to the Orang Laut. Singapore’s repressive free speech laws, top-down decision-making structure, and the manufactured sentiment that the country’s survival is tied to modernity all limit imagination for change.

Still, as Million contends, Indigeneity is not static; reclaiming Indigenous agency looks different across time. “There is a steady transformation that is our living change. The generations change and are changed,” Million writes.[45] Every media interview, public event, and mention of the Orang Laut in Parliament is a disruption of Singapore’s institutional memory, and constitutes a sustained form of action that over time can instigate significant cultural shifts. Change, after all, is woven together through non-linear acts of resistance.

Perhaps most importantly, the Orang Laut community is seeding the imagination for a different way of life in Singapore. For example, Firdaus emphasizes in interviews the principle of taking only what one needs when foraging,[46] reflecting an innate respect for and reciprocity with the non-human world. The materiality of Orang Laut cultural practices demonstrates that it is possible to demand agency and cultivate a different kind of world, even from within an unjust system.

Where most Singaporeans today see a landfill, the Orang Laut still see a home. I hope that one day the rest of us will, too, see Semakau as a symbol of what could be: a way of life that is slower, gentler, and centered around community.

Author’s Note

My goal in this project was not to provide a comprehensive account of Orang Laut history, nor of Singapore’s. Rather, I sought to engage in a practice of “historical recognition and witnessing,”[47] understanding that the active repression of the Orang Laut can only be subverted by an active act of remembering and listening. I am immensely grateful to Orang Laut descendants in Singapore who work tirelessly to capture their heritage. Although there are no Indigenous settlements remaining in Singapore today, I can build a more well-rounded understanding of my country’s history thanks to their efforts at preservation. (Thank you as well to G. W. and T. T. who helped me to access resources publicly available in Singapore which were not accessible from abroad.)

For this essay, I drew heavily on already-published interviews and documentaries (i) so as not to impose additional labor on the Orang Laut community, and (ii) to ensure that as much of the narratives here as possible are written by the Orang Laut, not simply for them. I encourage readers to continue following Orang Laut SG’s journey through Instagram (@oranglautsg) and/or their website.

Finally, I hope that foregrounding Southeast Asia—the region I call home—will help to broaden the geographical repertoire of the NAIS keyword archive beyond the United States. Indigenous struggles look different across contexts, yet colonial powers often enact violence through similar mechanisms, from forced assimilation to denialist histories. Identifying shared struggles can, in turn, strengthen transnational solidarity and generate new focal points for collective dissent and resistance. I choose to believe—indeed, we have no choice but to believe—that together, reclaiming a just future is possible.

Works Cited

Abdullah, Walid Jumblatt. “Selective History and Hegemony-Making: The Case of Singapore.”

International Political Science Review 39, no. 4 (2018): 473–86. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26956748.

Andaya, Leonard Y. Leaves of the Same Tree : Trade and Ethnicity in the Straits of Melaka. University of

Hawai’i Press, 2008.

Andaya, Leonard Y. “The Orang Laut and the Negara Selat (Realm of the Straits).” In 1819 &

Before: Singapore’s Pasts, edited by Kwa Chong Guan. ISEAS–Yusof Ishak Institute, 2021.

Barr, Michael D. “Singapore Comes to Terms with Its Malay Past: The Politics of Crafting a

National History.” Asian Studies Review 46, no. 2 (2021): 350–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/10357823.2021.1972934

Cornelius, Vernon. “Singapore River (historical overview).” National Library Board, 2016.

https://www.nlb.gov.sg/main/article-detail?cmsuuid=011fc400-0632-453b-8520-12ada317e263.

Ibrahim, Faridah. “Productivity campaign (1970s–1990s).” National Library Board, August 2019.

https://www.nlb.gov.sg/main/article-detail?cmsuuid=429f6f2d-6c74-49c3-a0b4-12643fe7c8db.

Ishak, Syahindah and Andrew Koay. “From ‘heaven’ to rubbish dump: S'porean family shares

memories of Pulau Semakau life.” Mothership, September 20, 2020. https://mothership.sg/2020/09/three-generations-pulau-semakau/amp/.

Kenyon, Peter. “Palestinians Face Pressure To Assimilate In Jerusalem.” NPR, December 13, 2017.

https://www.npr.org/2017/12/13/570603499/palestinians-face-pressure-to-assimilate-in-jerusalem.

Khoo, Vivienne. “An old man and the sea.” The Straits Times (via Newspaper SG), October 12, 1991.

https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/newspapers/digitised/page/stoverseas19911012-1.1.8.

Koh, Nancy. “Tranquil isle of charm.” New Nation (via Newspaper SG), October 20, 1981.

https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/newspapers/digitised/article/newnation19811020-1.2.50.1.

Lee, Lorraine. “A taste of what life was like on Pulau Semakau captured through photographs and

food.” Today Online, May 20 2024. https://www.todayonline.com/singapore/taste-what-life-was-pulau-semakau-captured-through-photographs-and-food.

Loh, Pei Ying. “Lawan Lupa (Fight the Forgetting): Orang Laut and Modes of Memory.”

Academia.edu, n.d. https://www.academia.edu/125758208/Lawan_Lupa_Fight_the_Forgetting_Orang_Laut_and_Modes_of_Memory.

Manjapra, Kris. Colonialism in Global Perspective. Cambridge University Press, 2020.

Million, Dian. “Epistemology.” In Native Studies Keywords, edited by Stephanie Nohelani Teves,

Andrea Smith, and Michelle Raheja. University of Arizona Press, 2015.

Nasir, Heirwin Mohd. “Stamford Raffles's career and contributions to Singapore.” National Library

Board, January 2019. https://www.nlb.gov.sg/main/article-detail?cmsuuid=3916c818-89dd-461b-9d45-81e27a08984a.

“Night Fishing at Sea with Singapore’s First Islanders.” Posted May 2, 2022, by Our Grandfather Story. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sKjTZJCyfw8.

Orang Laut SG. “We came from Pulau Semakau.” Last modified 2020. https://oranglaut.sg/.

“Plans for dumping rubbish offshore.” The Straits Times (via Newspaper SG), February 15, 1989.

https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/newspapers/digitised/article/straitstimes19890215-1.2.28.21.

Protecting Our Marine Spaces and Southern Islands. Singapore Parl Debates; Vol 95, Sitting No 93; March

20, 2023. https://sprs.parl.gov.sg/search/#/sprs3topic?reportid=oral-answer-3670.

PULAU SAKENG (Proposed landfill project). Singapore Parl Debates; Vol 61, Sitting No 11;

November 11, 1993.

https://sprs.parl.gov.sg/search/#/topic?reportid=004_19931111_S0004_T0005.

Raffles Museum of Biodiversity Research and Singapore Science Centre. “Map of Singapore Island.”

Accessed February 20, 2025.

https://habitatnews.nus.edu.sg/guidebooks/marinefish/text/117a.htm.

Rani, Rohani. “Life as an Orang Laut on Pulau Semakau.” Posted November 10, 2020, by Our

Grandfather Story. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GYD_e-GsgDY.

Reclamation at Pulau Semakau. Singapore Parl Debates; Vol 34, Sitting No 15; July 29, 1975.

https://sprs.parl.gov.sg/search/#/topic?reportid=034_19750729_S0005_T0029.

Saini, Nafeesa. “Meet the family spearheading the culinary revival of Orang Laut cuisine.” Prestige

Singapore, June 2, 2021.

Sani, Firdaus. “Foraging in Singapore’s seas: Keeping the Orang Laut traditions alive.” Posted April

5, 2024, by The Straits Times. YouTube. https://youtu.be/FY9N9qc1ti0?feature=shared.

Sani, Firdaus. “Is there a perfect Hari Raya?” Orang Laut SG Substack, May 19, 2021.

https://oranglautsg.substack.com/p/is-there-a-perfect-hari-raya.

SG 101. “1959-1965: Early Economic Strategies.” Last modified February 21, 2025.

https://www.sg101.gov.sg/economy/surviving-our-independence/1959-1965/.

“Singapore races to extend life of ‘Garbage of Eden’ Pulau Semakau, its only landfill site.” South

China Morning Post, July 28, 2023.

Singh, Prithpal. “Save Pulau Seking.” The Straits Times (via Newspaper SG), January 11, 1986.

https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/newspapers/digitised/article/straitstimes19860111-1.2.41.4.

Soh, Wee Ling. “The forgotten first people of Singapore.” BBC, August 24, 2021.

https://www.bbc.com/travel/article/20210824-the-forgotten-first-people-of-singapore.

The Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies. “The Stolen Generations.”

Accessed February 26, 2025. https://aiatsis.gov.au/explore/stolen-generations.

Tuck, Eve and K. Wayne Yang. “Decolonization is not a metaphor.” Decolonization: Indigenity,

Education & Society 1, no. 1 (2012): 1–40.

“Villagers have mixed feelings about leaving.” The Straits Times (via Newspaper SG), September 30,

1993. https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/newspapers/digitised/article/straitstimes19930930-1.2.58.3.2.

Waller, Edmund. “Keep P. Sakeng as it is.” The Straits Times (via Newspaper SG), October 22, 1993.

https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/newspapers/digitised/article/straitstimes19931022-1.2.68.6.2.

Wee, Vivienne and Geoffrey Benjamin. “Pulau Seking, the final link to pre-Raffles Singapore.”

Academia.sg (unpublished paper), n.d.

World Bank Group. “GDP per capita (current US$) - Singapore.” Accessed February 20, 2025.

https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD?locations=SG.

Yong, Clement. “‘Colonialism is not neutral’: Third public statue of Sir Stamford Raffles ignites

online debate.” The Straits Times, June 2, 2024. https://www.straitstimes.com/life/arts/colonialism-is-not-neutral-third-public-statue-of-sir-stamford-raffles-ignites-online-debate.

[1] Vivienne Wee and Geoffrey Benjamin, “Pulau Seking, the final link to pre-Raffles Singapore,” Academia.edu, n.d., 210-211, https://www.academia.edu/5343730/Vivienne_Wee_and_Geoffrey_Benjamin_Pulau_Seking_the_final_link_to_pre-Raffles_Singapore.

[2] “Singapore races to extend life of ‘Garbage of Eden’ Pulau Semakau, its only landfill site,” South China Morning Post, July 28, 2023, https://www.scmp.com/news/asia/southeast-asia/article/3229286/singapore-races-extend-life-garbage-eden-pulau-semakau-its-only-landfill-site.

[3] “Plans for dumping rubbish offshore,” The Straits Times (via Newspaper SG), February 15, 1989, https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/newspapers/digitised/article/straitstimes19890215-1.2.28.21.

[4] Reclamation at Pulau Semakau, Singapore Parl Debates; Vol 34, Sitting No 15; July 29, 1975, https://sprs.parl.gov.sg/search/#/topic?reportid=034_19750729_S0005_T0029.

[5] Wee Ling Soh, “The forgotten first people of Singapore,” BBC, August 24, 2021, https://www.bbc.com/travel/article/20210824-the-forgotten-first-people-of-singapore.

[6] Ilya Katrinnada, “The Orang Seletar: Rowing Across Changing Tides,” BiblioAsia 18, no. 1 (2022), https://biblioasia.nlb.gov.sg/vol-18/issue-1/apr-to-jun-2022/orang-seletar-changing-tides/.

[7] Leonard Y. Andaya, Leaves of the Same Tree : Trade and Ethnicity in the Straits of Melaka (University of Hawai’i Press, 2008), 51.

[8] Leonard Y. Andaya, “The Orang Laut and the Negara Selat (Realm of the Straits),” in 1819 & Before: Singapore’s Pasts, ed. Kwa Chong Guan (ISEAS–Yusof Ishak Institute, 2021), 47.

[9] Ibid, 49.

[10] Ibid, 52.

[11] “Map of Singapore Island,” Raffles Museum of Biodiversity Research and Singapore Science Centre, accessed February 20, 2025, https://habitatnews.nus.edu.sg/guidebooks/marinefish/text/117a.htm.

[12] Wee and Benjamin, “Pulau Seking, the final link to pre-Raffles Singapore,” 203.

[13] Rohani Rani, “Life as an Orang Laut on Pulau Semakau,” posted November 10, 2020, by Our Grandfather Story, YouTube, 5:00, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GYD_e-GsgDY.

[14] Firdaus Sani, “Is there a perfect Hari Raya?” Orang Laut SG Substack, May 19, 2021, https://oranglautsg.substack.com/p/is-there-a-perfect-hari-raya.

[15] Nancy Koh, “Tranquil isle of charm,” New Nation (via Newspaper SG), October 20, 1981, https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/newspapers/digitised/article/newnation19811020-1.2.50.1.

[16] Lorraine Lee, “A taste of what life was like on Pulau Semakau captured through photographs and food,” Today Online, May 20 2024, https://www.todayonline.com/singapore/taste-what-life-was-pulau-semakau-captured-through-photographs-and-food.

[17] Koh, “Tranquil isle of charm.”

[18] Heirwin Mohd Nasir, “Stamford Raffles's career and contributions to Singapore,” National Library Board, January 2019, https://www.nlb.gov.sg/main/article-detail?cmsuuid=3916c818-89dd-461b-9d45-81e27a08984a.

[19] “1959-1965: Early Economic Strategies,” SG 101, last modified February 21, 2025, https://www.sg101.gov.sg/economy/surviving-our-independence/1959-1965/.

[20] Walid Jumblatt Abdullah, “Selective History and Hegemony-Making: The Case of Singapore,” International Political Science Review 39, no. 4 (2018): 476, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26956748.

[21] “GDP per capita (current US$) - Singapore,” World Bank Group, accessed February 20, 2025, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD?locations=SG.

[22] Abdullah, “Selective History and Hegemony-Making: The Case of Singapore,” 478.

[23] Michael D Barr, “Singapore Comes to Terms with Its Malay Past: The Politics of Crafting a National History,” Asian Studies Review 46, no. 2 (2021): 351, https://doi.org/10.1080/10357823.2021.1972934.

[24] Clement Yong, “‘Colonialism is not neutral’: Third public statue of Sir Stamford Raffles ignites online debate,” The Straits Times, June 2, 2024, https://www.straitstimes.com/life/arts/colonialism-is-not-neutral-third-public-statue-of-sir-stamford-raffles-ignites-online-debate.

[25] Vernon Cornelius, “Singapore River (historical overview),” National Library Board, 2016, https://www.nlb.gov.sg/main/article-detail?cmsuuid=011fc400-0632-453b-8520-12ada317e263.

[26] “Villagers have mixed feelings about leaving,” The Straits Times (via Newspaper SG), September 30, 1993, https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/newspapers/digitised/article/straitstimes19930930-1.2.58.3.2.

[27] Syahindah Ishak and Andrew Koay, “From ‘heaven’ to rubbish dump: S'porean family shares memories of Pulau Semakau life,” Mothership, September 20, 2020, https://mothership.sg/2020/09/three-generations-pulau-semakau/amp/.

[28] Kris Manjapra, Colonialism in Global Perspective (Cambridge University Press, 2020), 150.

[29] Faridah Ibrahim, “Productivity campaign (1970s–1990s),” National Library Board, August 2019, https://www.nlb.gov.sg/main/article-detail?cmsuuid=429f6f2d-6c74-49c3-a0b4-12643fe7c8db.

[30] “The Stolen Generations,” The Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, accessed February 26, 2025, https://aiatsis.gov.au/explore/stolen-generations.

[31] Peter Kenyon, “Palestinians Face Pressure To Assimilate In Jerusalem,” NPR, December 13, 2017,

https://www.npr.org/2017/12/13/570603499/palestinians-face-pressure-to-assimilate-in-jerusalem.

[32] PULAU SAKENG (Proposed landfill project), Singapore Parl Debates; Vol 61, Sitting No 11; November 11, 1993, https://sprs.parl.gov.sg/search/#/topic?reportid=004_19931111_S0004_T0005.

[33] Pei Ying Loh, “Lawan Lupa (Fight the Forgetting): Orang Laut and Modes of Memory,” Academia.edu, n.d., https://www.academia.edu/125758208/Lawan_Lupa_Fight_the_Forgetting_Orang_Laut_and_Modes_of_Memory.

[34] Protecting Our Marine Spaces and Southern Islands, Singapore Parl Debates; Vol 95, Sitting No 93; March 20, 2023, https://sprs.parl.gov.sg/search/#/sprs3topic?reportid=oral-answer-3670.

[35] “We came from Pulau Semakau,” Orang Laut SG, last modified 2020, https://oranglaut.sg/.

[36] Prithpal Singh, “Save Pulau Seking,” The Straits Times (via Newspaper SG), January 11, 1986, https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/newspapers/digitised/article/straitstimes19860111-1.2.41.4.

[37] Edmund Waller, “Keep P. Sakeng as it is,” The Straits Times (via Newspaper SG), October 22, 1993, https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/newspapers/digitised/article/straitstimes19931022-1.2.68.6.2.

[38] Vivienne Khoo, “An old man and the sea,” The Straits Times (via Newspaper SG), October 12, 1991, https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/newspapers/digitised/page/stoverseas19911012-1.1.8.

[39] Ibid.

[40] Nafeesa Saini, “Meet the family spearheading the culinary revival of Orang Laut cuisine,” Prestige Singapore, June 2, 2021, https://www.prestigeonline.com/sg/people/meet-the-family-reviving-the-culinary-heritage-of-orang-laut/.

[41] “Night Fishing at Sea with Singapore’s First Islanders,” posted May 2, 2022, by Our Grandfather Story, YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sKjTZJCyfw8.

[42] “Night Fishing at Sea with Singapore’s First Islanders,” posted May 2, 2022, by Our Grandfather Story, YouTube, 3:15, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sKjTZJCyfw8.

[43] Ibid, 2:28.

[44] Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang, “Decolonization is not a metaphor,” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 1, no. 1 (2012): 1–40, https://clas.osu.edu/sites/clas.osu.edu/files/Tuck%20and%20Yang%202012%20Decolonization%20is%20not%20a%20metaphor.pdf.

[45] Dian Million, “Epistemology,” in Native Studies Keywords, ed. Stephanie Nohelani Teves, Andrea Smith, and Michelle Raheja (University of Arizona Press, 2015), 344.

[46] Firdaus Sani, “Foraging in Singapore’s seas: Keeping the Orang Laut traditions alive,” posted April 5, 2024, by The Straits Times, YouTube, 1:45, https://youtu.be/FY9N9qc1ti0?feature=shared.

[47] Manjapra, Colonialism in Global Perspective, 4.