Photograph

by Pedro Martinez-Pinto

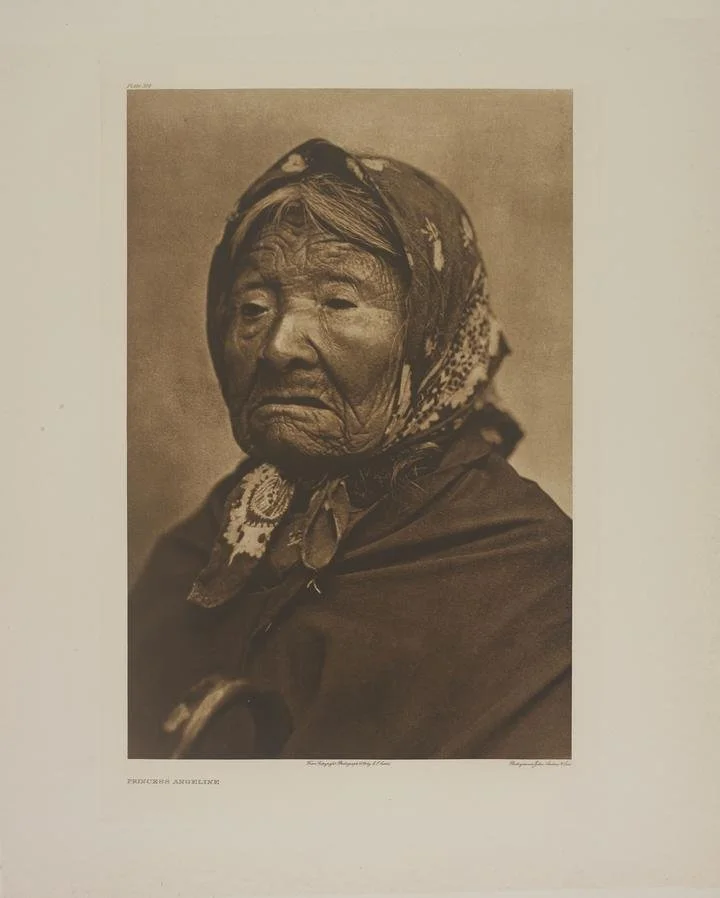

“Princess Angeline” (Edward Curtis)

This photograph of Kikisoblu, known in the archive as “Princess Angeline,” was taken in 1895 by Edward Curtis– the very same Curtis who would, years later, become famous for his expansive documentation of Native Americans and their “primitive customs and ancient beliefs.” Kikisoblu was the daughter and last surviving child of Chief Si’ahl, of the Duwamish and Suquamish tribes that resided in what is now known, in the colonizer’s language, as Seattle. Her portrait evokes a certain sadness: her mouth is curled into a permanent frown, her skin looks rough and wrinkled, and her eyes are hidden behind dark slits. Curtis knew of her fame when he took the photograph: she was “the old crone, the living mummy, the gnarled Indian, the hag, and the face frozen in time” (Edward S. Curtis: Enduring Legacy). Within the historical archive, descriptions of Angeline center on her appearance and living conditions:

“She was nearly blind, her eyes a quarter-rise slit without noticeable lashes. Said to have a single tooth, she was famous for her ugliness.”

“Angeline lived in a shack down among the greased piers and coal bunkers of Seattle. The cabin had two rooms and was dank inside. “If you wanted to dump a bucket of cooking oil or a rusted stove or a body, this was the place to do it. It smelled of viscera, sewage, and raw industry” (Edward S. Curtis: Enduring Legacy).

These descriptions make evident Kikosoblu’s positioning in the archive: she was viewed as an exhibit, something to frame and capture; her ugliness and squalid state of living was something to gawk at. A circus freak: “she was great fun. They taunted the gnarled Indian, threw rocks at her” (Edward S. Curtis: Enduring Legacy). Curtis’ desire, supposedly, was to capture an old, strong, and unwavering face from the past. With the photograph of her, he hoped to “convey a face that had seen worlds change, forests leveled, tidelands filled, people crushed” (Edward S. Curtis: Enduring Legacy). What people crushed? That is the question. Rather than seeing Kikisoblu for what she represented now, in the present, Curtis hoped to freeze her image in time– the face that had seen worlds– before she disappeared. He paid her a dollar to take her image. This was the image I had seen before, in a middle school class called “Washington State History.” I remember she was mentioned just once, ever so briefly.

Science and the Photograph

Photography—or the act of taking a photograph— comes from the Greek words phōs (φῶς), meaning "light", and graphê (γραφή), meaning "drawing" or "writing." The word photograph then is inherently relational, tying the person behind the camera to the making of a “drawing with light.” From its conception in 1839, the photographic form brought together artistic expression and the “power” of scientific knowledge in a way that blurred the line between art and objectivity. Perhaps most importantly, the photograph made possible a new means of acquiring knowledge, for it was now possible to “study” the anatomy of a dead spider in a way that allowed one to “follow and examine” every filament and every duct, “as in nature” (Daniel). I’ll revisit this idea of making nature knowable. For now, suffice it to say photographs were seen as a means to capture the world and the role of the photographer was theoretically, as time progressed, minimized to a type of removed observant– only there to capture the world as it existed. Of course, in practice the photographer could not wield an instrument like the camera without imposing some kind of purpose or intention onto it. After all, “photographs suggest meaning through the way in which they are structured, for representational form makes an image accessible and comprehensible to the mind, informing and informed by a whole hidden corpus of knowledge that is called on through the signifiers in the image” (Vizenor 147). Put simply, a photograph is not purely an objective image. Rather, it is a representational form created by the photographer. The photograph's structure (chosen intentionally by the photographer) and what it does for the viewer creates meaning that extends beyond the objective documentation of the world. There’s more to the photographic medium than its ability to “follow and examine” every filament and every duct of a spider (Daniel).

It is these very features of the photograph which historically made it a useful, if not central tool, in the colonial encounter. Following the invention of the Daguerreotype, photography began to spread into the colonial arsenal, carried along by the practice of “science”: “In Africa, as in most parts of the dispossessed, the camera arrived as part of the colonial paraphernalia, together with the gun and the bible…” (Cole). The gun and the bible are both elements of the colonial arsenal which have a physical basis. The gun on its own is what allows war, violence, and brute force to be enacted in the colonial encounter– often making possible the stealing of land and resources. And the bible is what facilitates the further assimilation of indigenous peoples into the settler colonial culture.

The photograph, not unlike the bible, plays a type of secondary role in the progression of colonialism; however, its basis is not necessarily physical but ideological. In “When the Camera Was a Weapon of Imperialism…” Cole describes a photograph taken in what is now known as Nigeria– formerly “Yorubaland”; it is of the Yoruba people under British rule.

Of utmost importance in this image is the visibility it provides. The Yoruba King (the one in the center-right of the image) is sitting solemnly. His facial features are exposed and the beads draping off his head are partitioned. All the Yoruba in the photograph are underexposed, their faces are dark and they morph together while those of the British men positioned in the center of the frame are clear– their faces stand out. On the part of the photographer this concealment simultaneously reveals– this is the meaning created by its structure– a display of power within the image itself. Cole writes that the image is also unusual because the Yoruba King (the Oba) is meant to be concealed in public with the beads from his head shrouding his face; they are meant to give him a “divine aspect” (Cole). This is why the crowd of Yoruba in the front of the image is turning towards the camera, as if blinded by the King. The image then, whether or not the photographer intended to, is a means by which to subvert the Yoruba right to practice their religion. It is also a means by which to make everything formerly unknowable about the Yoruba “seen and cataloged” under the rule of the British empire.

Through this image, the photograph’s operation as a colonial tool becomes blatantly evident; it can be a method of acquiring a semblance of control and understanding of “the other” inherent to colonialism: “the dominant power decided that everything had to be seen and cataloged, a task for which photography was perfectly suited. Under the giant umbrella of colonialism, nothing would be allowed to remain hidden from the imperial authorities” (Cole). This element of the photograph– its ability to make things seen and cataloged– is what gave it power in the colonial encounter.

From its inception, the Daguerreotype and naturally so too the photograph that would come later served a dual purpose of functioning as an artistic medium but also a scientific one. In fact, “Daguerre promoted his invention on both fronts” (Daniel). The photograph, from its inception, was destined to become intertwined with colonialism. Its inherent relation to science in the European context is what allowed the photograph to flourish as part of the colonial “paraphernalia” (Cole) in many different historical contexts. Kris Manjapra, in “Colonialism in Global Perspective,” writes that the emergence of natural science in Europe became an important tool in colonizing acts globally. Consequently, the “plants, animals, and minerals already woven into the lifeworlds of other human communities were assimilated into the system that Linnaeus described as ‘Man entering the theater of the world’” (Manjapra). Critical to science was its ability to do just that– “assimilate” people, things, and ways of life into a system understood by western empires. It was a system that allowed for ultimate control. Science allowed imperial states to “forcibly and militarily place their colonies and subject peoples in measurable relation to other colonies and subject peoples around the world.” Furthermore, “colonial power used practices of cataloguing, measuring, auditing, and containerizing in order to transfer laborers and commodities between colonial locations, and across cultural and political borders” (Manjapra). In essence, science and its ability to catalogue, measure, audit, and containerize tied what was “out there” to what was “in here” (the colonial center or location of power) throughout the process of colonization.

Edward Curtis and US Colonization

The photograph, in later colonial contexts, evolved to having a function beyond simple categorization and control. It began to allow for ideological functions critical to the erasure of colonized peoples, especially in the context of the United States. Edward Curtis, throughout his career and beginning with his photographic capture of Angeline and her “face frozen in time” sought out to depict and archive “untouched” native life that would soon become extinct. Behind this fascination and desire to record Native Americans was an attempt to “collect information on a people they judged incapable of recording their own histories” (Romero). This drive to record “ancient” and “primitive” culture was central to the emerging idea of “Indians” as “vanishing.” Within the US, “ ‘the vanishing Indian’ was used to elide the very real way that US policies led to American Indian deaths: ‘real and actual Indian peoples and their cultures vanished into an image designed, constructed, and manufactured” (Romero). Curtis and his photographs were central to that project.

His artistry, the camera he used, the way he edited his images, all contributed to a look of fading. Native Americans (see above) were on their way out, fading into nothingness. Beautiful, but long gone.

The Indigenous Photograph

What the photograph of Princess Angeline could not ever convey–rather intentionally–was her agency, strength, and life force carrying into the present moment– a moment where she was a source of resistance and a reminder of indigenous sovereignty in the face of settler colonialism. She wasn’t just an “old hag” like she was in the photographic record. She was Coast Salish, and her presence in Seattle and her little dilapidated shed were active sites of resistance. She chose to stay following the Treaty of Point Elliott, which saw the removal of indigenous peoples from their ancestral homelands in order to make room for white settlers. Angeline did not move despite the treatment she faced from white settlers. They would throw rocks at her, but she would throw them back: “under those layers of filthy skirts, Angeline carried rocks for self-defense. She didn’t leave the shack without ammunition. She didn’t hide or retreat, but instead would sink an arthritic hand into one of her many pockets, find a stone and let it rip” (Edward S. Curtis: Enduring Legacy). Curtis’ portrait undid that history and reduced it to a face– old, empty, historical, wrinkled, strong, angry. Just there.

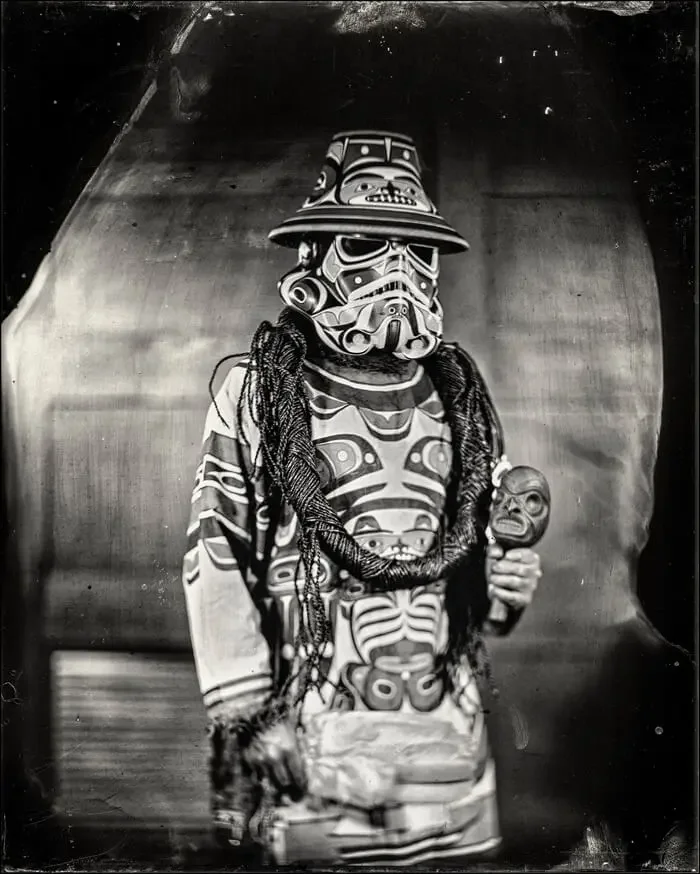

Will Wilson, in his indigenous photographic project– the Critical Indigenous Photographic Exchange– seeks to undo that facet of Curtis’ work. He used the same medium as Curtis, but changed his methodology to one of collaboration. There are no photographic subjects, only “collaborators” (Wilson). And there are no methods or structures which impose a meaning dictated by the photographer. Rather, the photos and what is in them are chosen by the collaborators themselves.

Like in the photograph above, the photographs made by Wilson complicate our understandings of what it is to be Native within the photographic archive– the answer to that is unique to everyone who chooses to participate. Through the use of Curtis’ techniques, Wilson puts the images in dialogue with those of the past. Both the photographer and the photographed resist the “vanishing Indian” and the simplification inherent to the colonial photograph. Time passes– the stormtrooper influence above shows us that indigenous people are surviving and adapting despite colonialism. They are here in the present, not back in Curtis’ ethnographic images. Wilson also allows them to speak in his “talking tintype” project, where collaborators are able to make change within the archive itself. They’re able to show themselves and tell their own stories. Such is the power of the indigenous photograph. Imagine if Angeline could have reached us through the frame to speak to us– of what mattered to her, of who she was, of what made her angry, and of why she decided to stay. Cole writes that “photography writes with light, but not everything wants to be seen. Among the human rights is the right to remain obscure, unseen and dark” or at the very least, seen in one's own light.

Bibliography

Cole, Teju. “When the Camera Was a Weapon of Imperialism. (And When It Still Is.).” The New York Times, 6 Feb. 2019. NYTimes.com, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/02/06/magazine/when-the-camera-was-a-weapon-of-imperialism-and-when-it-still-is.html.

Daniel, Malcolm. “Daguerre (1787–1851) and the Invention of Photography | Essay | The Metropolitan Museum of Art | Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History.” The Met’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/dagu/hd_dagu.htm. Accessed 6 Feb. 2025.

“Edward S. Curtis: Enduring Legacy.” The Gallery of Photographic History, 8 Aug. 2020, https://robc224.wordpress.com/2020/08/07/edward-s-curtis/.

Egan, Shannon. “‘Yet in a Primitive Condition’: Edward S. Curtis’s North American Indian.” American Art, vol. 20, no. 3, 2006, pp. 58–83. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.1086/511095.

Manjapra, Kris, editor. “Science.” Colonialism in Global Perspective, Cambridge University Press, 2020, pp. 127–43. Cambridge University Press, https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108560580.007.

“Photography.” IMMA, https://imma.ie/what-is-art/series-3-materials-methodologies/photography/. Accessed 6 Feb. 2025.

RICKARD, JOLENE. “Sovereignty: A Line In The Sand | Aperture | Summer 1995.” Aperture | The Complete Archive, https://issues.aperture.org/article/1995/2/2/sovereignty-a-line-in-the-sand. Accessed 5 Feb. 2025.

Romero, Channete. “The Politics of the Camera: Visual Storytelling and Sovereignty in Victor Masayesva’s Itam Hakim, Hopiit.” Studies in American Indian Literatures, vol. 22, no. 1, 2010, pp. 49–75. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1353/ail.0.0125.

Wilson, Will. Https://Willwilson.Photoshelter.Com/Index. https://willwilson.photoshelter.com/index. Accessed 28 Feb. 2025.

Vizenor, Gerald Robert. Fugitive Poses : Native American Indian Scenes of Absence and Presence. University of Nebraska Press, 1998.