Artist Statement: A Letter for Many Worlds

Dear Reader:

I created this zine as an invitation—to reflect, to question, and to imagine alongside me. I first encountered the idea of the pluriverse in a class (shoutout: Placing Anthropocene Stories)–while grappling with my own questions about belonging, resistance, and the futures we dare to imagine. As someone navigating the in-between spaces of identity, migration, dispossession, and history, the pluriverse felt less like an abstract theory and more like a language for the world I already knew—one where many realities coexist, sometimes overlapping, sometimes colliding.

The concept of the pluriverse has been shaped by many scholars and communities, including Arturo Escobar (2018), Ashish Kothari (2019), Walter D. Mignolo (2018), Boaventura de Sousa Santos (2019), Marisol de la Cadena and Mario Blaser (2018) and the Zapatistas, among others. Their work, alongside the lived struggles of countless communities resisting colonialism and capitalism, has informed my understanding of the pluriverse. This zine acknowledges those voices while also emphasizing that the pluriverse is always in the making—crafted by many named and unnamed actors who dare to dream of other worlds.

The color palette of my zine was inspired by the cover image, which, although the artist is unknown, appears to pay tribute to the Zapatista movement and the campesinos (farm workers) who are integral to enacting other worlds. The vibrant tones reflect the movement’s deep ties to land, struggle, and Indigenous resistance.

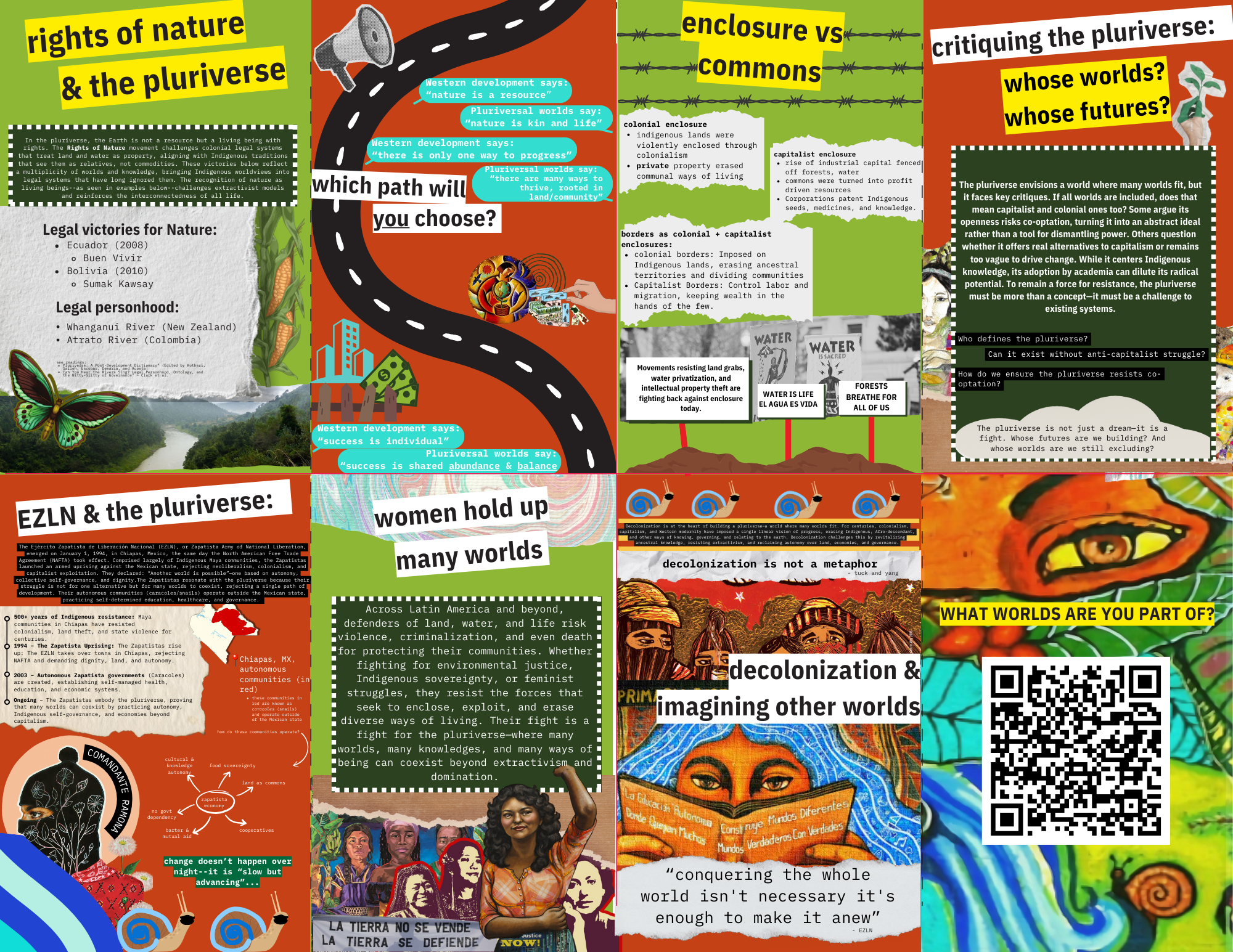

In effort to honor the Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional (EZLN), I dedicated a panel to explaining their significance. The symbology of the snail (caracol) is particularly important in my zine. The caracoles are not only the name of the Zapatista autonomous communities but also represent the slow, spiraling movement of their struggle—one that resists the linear, fast-paced model of capitalist development. As Subcomandante Marcos notes, the Indigenous people of Chiapas have long revered the conch, using it to summon the community and listen to distant worlds (Casanova 2010). This symbolism aligns with the Zapatista philosophy of interconnection, where autonomy is not about isolation but about building networks of solidarity. Just as the conch carries sound across great distances, the Zapatista movement and the idea of the pluriverse resonate far beyond Chiapas, inspiring struggles for self-determination and decolonial futures worldwide. The snail, in particular, embodies the Zapatista motto: “Lento, pero avanzo”—slowly but advancing (Tucker 2018). It represents a form of resistance that is patient, deliberate, and enduring. Change does not always happen in abrupt revolutions but in steady, continuous movement. Through my zine, I aim to honor these connections, emphasizing that another world is not only possible but already in motion—slowly but advancing.

Through this zine, I wanted to honor the many women who have long been at the forefront of movements for alternative futures—the ones who have carried histories, dreams, and struggles on their backs while daring to imagine something different. In the panel “Women hold up many worlds,” I included a collage of Indigenous and Afro-Indigenous women who have been at the forefront of resistance movements. As I assembled their images, I thought about the stories I’ve heard, the lessons I’ve learned from the women in my own life, and the ways their strength continues to carve out possibilities for all of us.

I also wanted to include how decolonization plays a role with the pluriverse. I included a panel on decolonization in my zine on the pluriverse because the two concepts are deeply intertwined. The pluriverse challenges the dominance of a single worldview by uplifting many ways of knowing, being, and relating to the world—an inherently decolonial act. However, as scholars like Melanie Yazzie and Cutcha Risling Baldy (2018) argue–building on Tuck and Yang’s work (2012)–, “decolonization is not a metaphor to be taken up within existing settler agendas.” It is not merely a conceptual framework but an active struggle against colonial structures that continue to shape our world. At the same time, Yazzie and Baldy remind us that, despite differing approaches to decolonization and resistance, what remains vital is the expansive interconnectedness forged through these struggles. Decolonization is not isolated to one region or community; it is relational, built through solidarities that transcend borders. This aligns with Michelle Daigle and Margaret Ramirez’s (2019) call to center solidarity by “revisioning and re-embodying a politics of place by interweaving spatial practices of resistance, refusal, and liberation.” In the context of my zine, this means recognizing that the pluriverse is not just about envisioning multiple worlds—it is about actively resisting systems of domination and creating spaces where alternative ways of living can thrive. Including the snails in this panel visually reinforces the idea that decolonization is not a straightforward or linear journey. It acknowledges that while progress may be slow, progress is not stagnant, and is occurring through acts of refusal and the reimagining of our relationships to our land, community, and knowledge.

I included a panel on the Rights of Nature because, to me, the pluriverse isn’t just about human diversity—it’s also about the lands, waters, and beings that have always been part of our worlds, even as colonial and capitalist frameworks try to sever those ties. I grew up understanding that nature isn’t something separate from us; it is intertwined with our histories, struggles, and futures. Recognizing the Rights of Nature affirms what many Indigenous communities have always known: that rivers, mountains, and forests are not just resources to be extracted but living entities with their own agency and rights. Including this panel felt essential because the pluriverse isn’t just about imagining many worlds; it’s about protecting the ones that already exist and recognizing the legal efforts that are working toward this vision.

Furthermore, I used a call and response format—contrasting “The Pluriverse says” with “Western Development says”—to highlight the fundamental tensions between dominant Western development models and the pluriverse. The pluriverse is not just about acknowledging multiple worldviews; it actively challenges the universalizing logic of Western modernity, which assumes that progress, economic growth, and technological advancement follow a single, linear path. By structuring the panel in a call and response format, I wanted to make these contradictions explicit and invite the reader to critically engage with these opposing frameworks. I also felt like the call and response as a structure also mirrors the relationality at the heart of the pluriverse. Unlike Western epistemologies that often prioritize fixed, authoritative knowledge, the pluriverse is about dialogue, reciprocity, and the coexistence of multiple truths (Escobar 2018). In using this format, I wanted to reflect that dynamic engagement—rather than imposing a singular narrative, the zine itself participates in an ongoing conversation. By reading both sides, the audience is invited to critically reflect on how development has been framed and to consider alternative ways of imagining the future.

A similar contrast appears in my side-by-side comparison of Enclosure vs. The Commons. Enclosure—the privatization of land, resources, and knowledge—has been a fundamental tool of colonial and capitalist expansion, disrupting collective ways of being and reinforcing scarcity and competition. In contrast, the commons represents a different way of organizing life—one centered on shared stewardship, reciprocity, and abundance. By juxtaposing these concepts, I emphasize that the pluriverse is not just about envisioning many worlds—it is about actively resisting the forces that enclose, extract, and dispossess.

I struggled with whether to include critiques of the pluriverse. On one hand, I love the expansiveness it offers. But I also know that not every world is liberatory, and that these ideas—like all ideas—can be co-opted. I want you to wrestle with these tensions alongside me, to ask: how do we imagine otherwise while remaining critical? Engaging with these critiques is essential to avoid romanticizing the pluriverse or treating it as an abstract, universally liberatory idea. By including these perspectives, I encourage deeper reflection on how the pluriverse can be mobilized in ways that are genuinely transformative rather than co-opted by existing power structures. One key critique is that the pluriverse, if not carefully articulated, can be diluted into a framework that merely accommodates diversity without challenging the underlying systems of capitalism, colonialism, and state power. Scholars like Melanie Yazzie (2018) and Leanne Betasamosake Simpson (2017) caution that concepts like decolonization—and by extension, the pluriverse—can sometimes be taken up in ways that reinforce settler and capitalist agendas rather than dismantling them. Similarly, some argue that without a clear commitment to dismantling oppressive structures, the pluriverse risks becoming a depoliticized celebration of difference rather than a radical project of transformation (de la Cadena and Blaser 2018). Another critique is that not all worlds within the pluriverse are necessarily liberatory (Masquelier 2022). If the pluriverse means allowing many ways of being to coexist, does that include oppressive or harmful systems? How do we differentiate between worlds that uphold justice and those that reinforce domination? By engaging with these critiques, I highlight that the pluriverse must be more than an abstract celebration of multiplicity—it must be an active struggle for autonomy. Including these critiques strengthens the zine by making space for critical engagement rather than passive acceptance. It reinforces that the pluriverse is not a static or perfect concept but an ongoing process—one that must be shaped by the struggles, solidarities, and refusals of those working toward genuinely transformative futures.

Through this zine, I seek to honor the struggles, solidarities, and refusals that are shaping the pluriverse in real time. Another world is not only possible—it is already in motion, slowly but advancing.

As you turn these pages, I hope you find yourself questioning, imagining, remembering. What stories do you carry? What worlds do you dream into being? What will you add to it?

In solidarity,

Naiset Perez

References

Cadena, Marisol de l., and Mario Blaser, eds. 2018. A World of Many Worlds. Duke University Press.

Daigle, Michelle, and Margaret Ramirez. 2019. “Decolonial Geographies.” In Keywords in Radical Geography: Antipode at 50, edited by Tariq Jazeel and The Antipode Editorial Collective. Wiley.

Escobar, Arturo. 2018. Designs for the Pluriverse: Radical Interdependence, Autonomy, and the Making of Worlds. Duke University Press.

Gonzalez Casanova, Pablo. 2010. “The Zapatista “caracoles”: Networks of resistance and autonomy.” Socialism and Democracy 19 (3): 79-92. doi:10.1080/08854300500257963.

Kothari, Ashish, Ariel Salleh, Arturo Escobar, Federico Demaria, and Alberto Acosta, eds. 2019. Pluriverse: A Post-development Dictionary. Tulika Books and Authorsupfront.

Masquelier, Charles. 2022. “Pluriversal intersectionality, critique and utopia.” The Sociological Review 70, no. 3 (March). https://doi-org.dartmouth.idm.oclc.org/10.1177/00380261221079115.

Mignolo, Walter D. 2018. “Foreword. On Pluriversality and Multipolarity.” In Constructing the Pluriverse: The Geopolitics of Knowledge, edited by Bernd Reiter. Duke University Press.

Santos, Boaventura de S., and Bruno S. Martins, eds. 2021. The Pluriverse of Human Rights: The Diversity of Struggles for Dignity. Routledge.

Simpson, Leanne B. 2017. As We Have Always Done: Indigenous Freedom Through Radical Resistance. University of Minnesota Press.

Tuck, Eve, and K. W. Yang. 2012. “Decolonization is not a metaphor.” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 1 (1): 1-40.

Tucker, Duncan. 2018. “¿Viva la Revolución? What happened to Mexico’s Zapatista Movement...” Latino Life. https://www.latinolife.co.uk/articles/viva-la-revolucion-what-happened-mexicos-zapatista-movement.

Yazzie, Melanie K., and Cutcha Risling Baldy. 2018. “Introduction: Indigenous Peoples and the Politics of Water.” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education, and Society 7, no. 1 (September).